Born Maria Salomea Skłodowska on November 7, 1867, in Warsaw, Poland, Marie Curie grew up in a land under Russian occupation, where opportunities for women in science were almost nonexistent.

Her father, a physics teacher, nurtured her love for learning, often bringing scientific instruments home when schools lacked resources. Even as a child, she had a fierce determination to pursue knowledge.

But life was far from easy. At just ten years old, she lost her mother to tuberculosis, and her family struggled financially. Marie worked as a governess to support her sister’s education, keeping alive her own dream of studying science.

“We must have perseverance, and above all confidence in ourselves,”

she later reflected—a mantra she had lived since youth.

Paris — A New World of Possibilities

In 1891, she adopted the French version of her name, Marie and moved to Paris to study at the Sorbonne, enduring poverty so severe that she sometimes fainted from hunger.

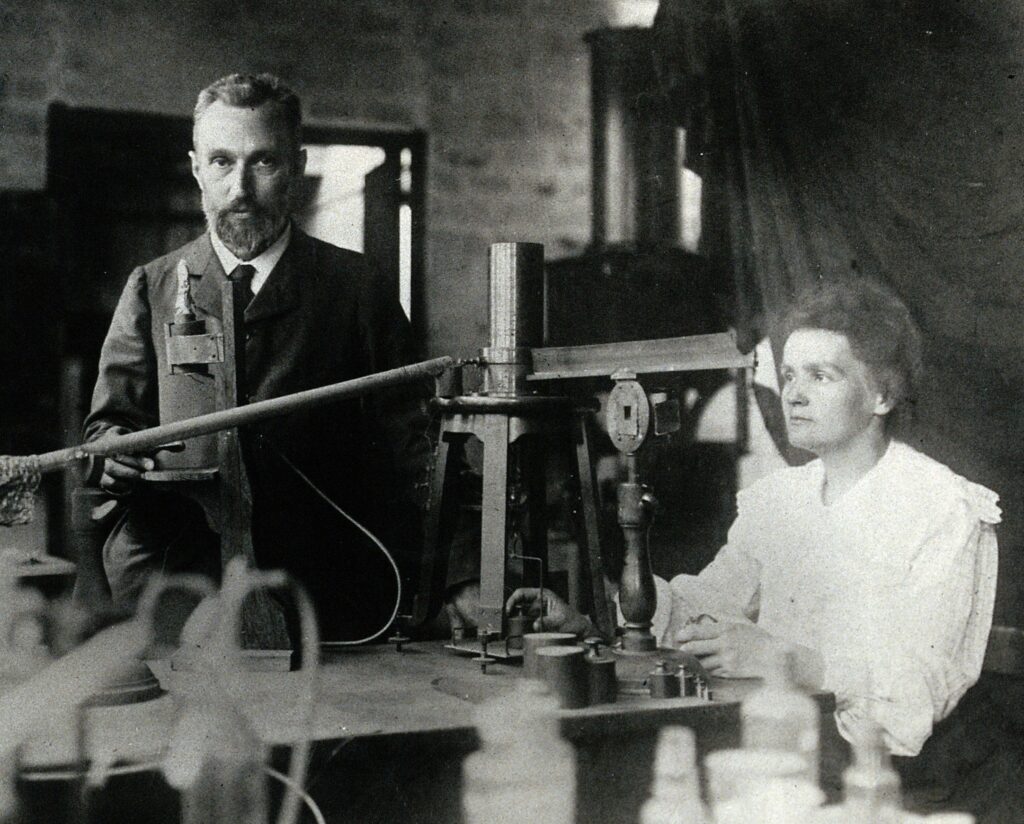

Yet, she graduated top of her class in physics in 1893 and earned another degree in mathematics the following year. In 1894, she met Pierre Curie, a brilliant scientist whose devotion to research matched her own.

The two married in 1895 and formed one of the most iconic scientific partnerships in history. Their marriage was not of luxury but of shared purpose, with Marie recalling:

“It was like a new world opened to me, the world of science, which I was at last permitted to know in all liberty.”

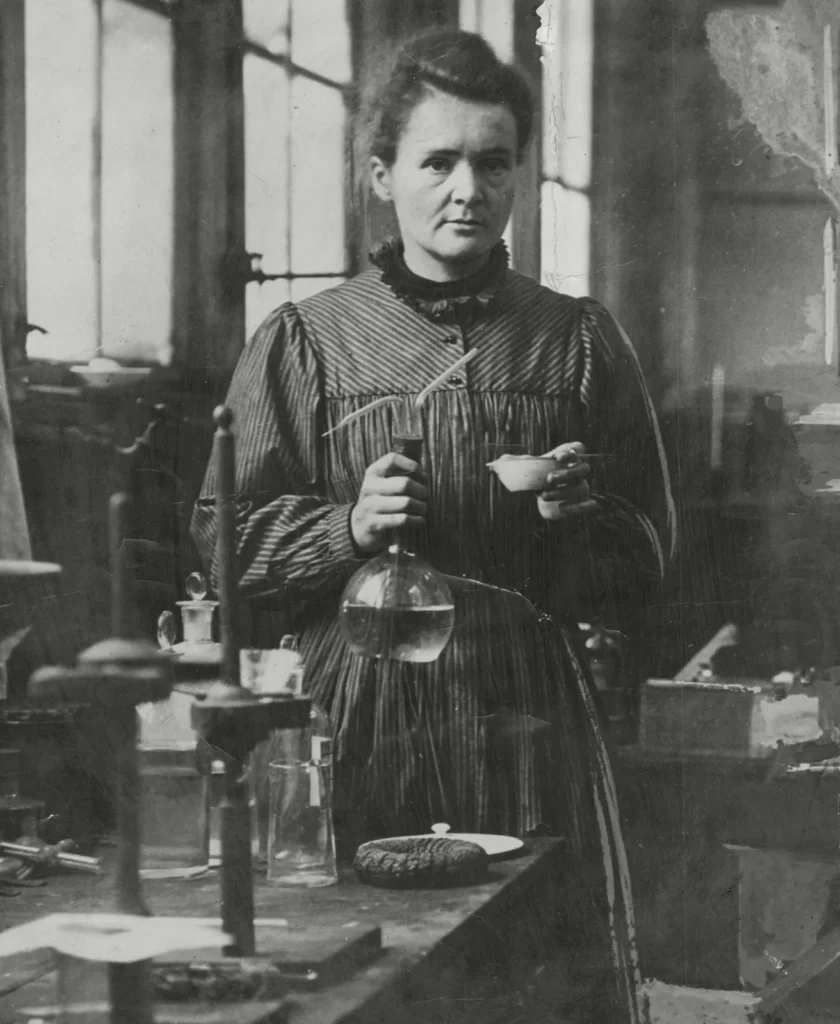

The Discovery That Changed Science

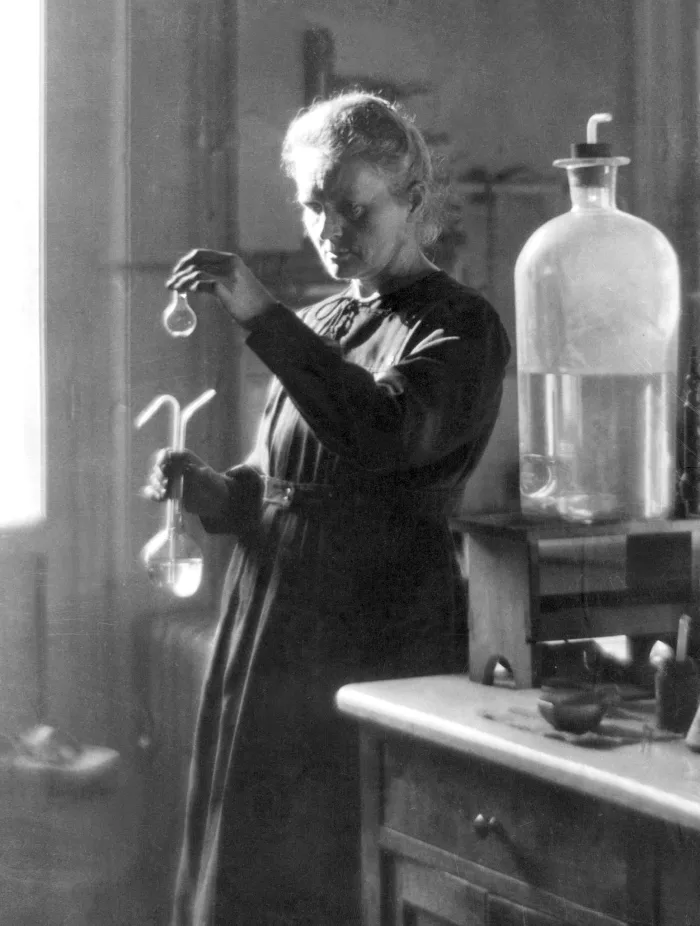

In 1898, the Curies announced the discovery of polonium, named after Marie’s homeland, and radium. Their research unlocked the mysterious phenomenon they called radioactivity—a term Marie coined herself.

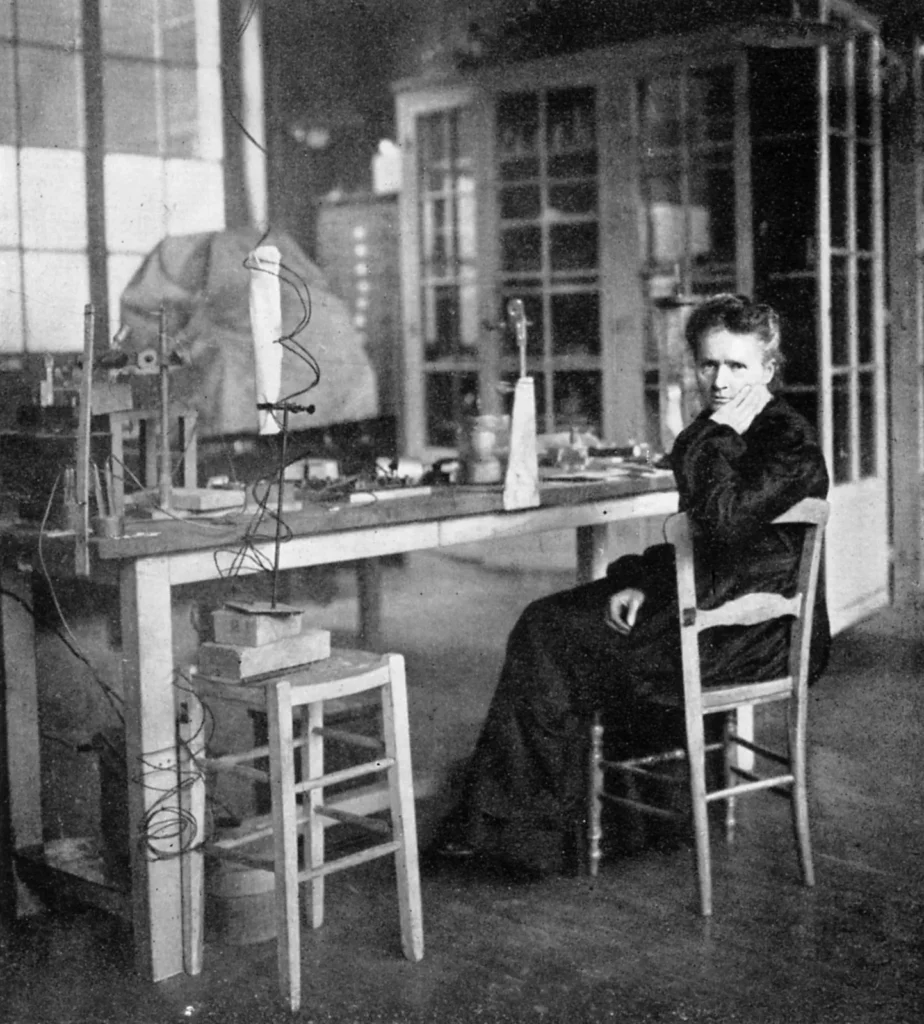

It opened up an entirely new field of research in physics and chemistry. Their work was painstaking. Marie processed tons of pitchblende ore in a makeshift lab, stirring boiling cauldrons for hours.

“One never notices what has been done; one can only see what remains to be done,”

she said, never satisfied with resting on past achievements.

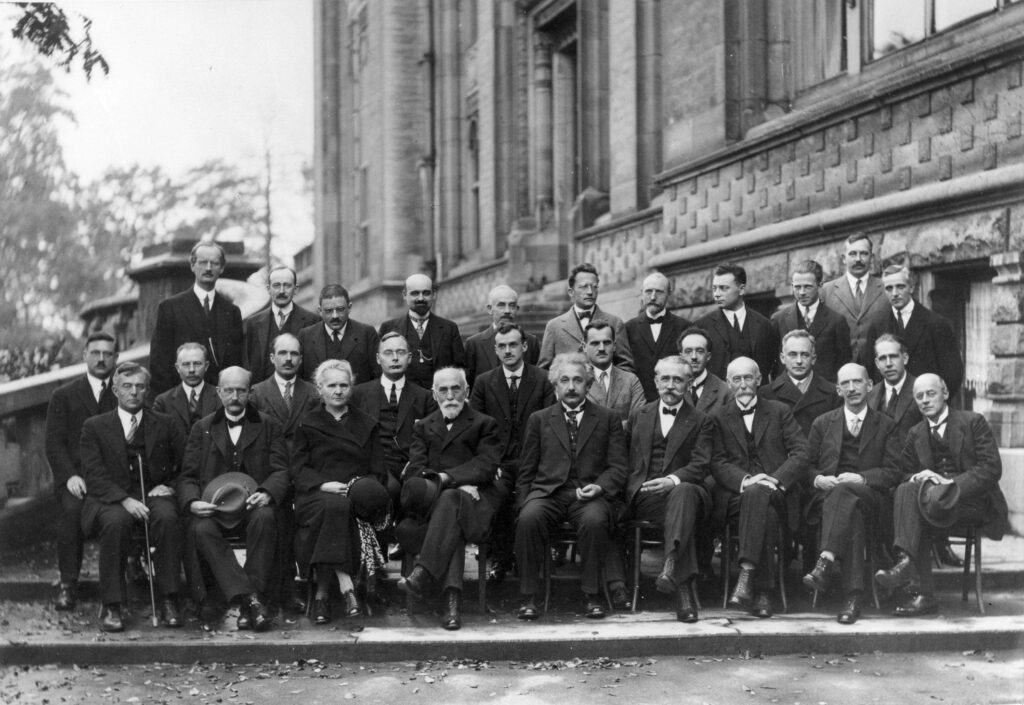

In 1903, Marie and Pierre shared the Nobel Prize in Physics with Henri Becquerel, making Marie the first woman to win a Nobel Prize.

Loss and Unshakable Resolve

Tragedy struck in 1906 when Pierre died in a street accident, leaving Marie devastated. Yet she stepped into his teaching position at the Sorbonne, becoming the first female professor in its history.

She continued her research and, in 1911, won her second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry—an unprecedented achievement. To this day, she remains the only person to win Nobel Prizes in two different sciences.

When scandal erupted over her alleged personal life, she refused to be derailed:

“Be less curious about people and more curious about ideas,”

she famously remarked.

War, Service, and Legacy

During World War I, Marie developed mobile X-ray units, known as “Little Curies”, bringing life-saving diagnostics to soldiers at the front. She trained nurses and drove the units herself, risking her safety to serve humanity.

In her later years, her exposure to radiation—then little understood—damaged her health. She died on July 4, 1934, of aplastic anemia, likely caused by years of working with radioactive materials without protection.

Her notebooks are still radioactive and stored in lead boxes.

Her Immortal Light

Marie Curie founded the Radium Institute in Paris in 1914, which became a leading center for medical research. She also trained a new generation of scientists, including her daughter Irène Joliot-Curie, who also won a Nobel Prize.

Marie Curie’s legacy transcends science. She paved the way for women in research, inspired generations to pursue knowledge fearlessly, and proved that perseverance can change the world. Her simple yet profound belief remains timeless:

“I am among those who think that science has great beauty. A scientist in his laboratory is not only a technician: he is also a child placed before natural phenomena which impress him like a fairy tale.”

“I am one of those who think that humanity will draw more good than evil from new discoveries.”

“We must believe that we are gifted for something, and that this thing, at whatever cost, must be attained.”

“We must not forget that when radium was discovered no one knew that it would prove useful in hospitals. The work was one of pure science. And this is a proof that scientific work must not be considered from the point of view of the direct usefulness of it.

It must be done for itself, for the beauty of science, and then there is always the chance that a scientific discovery may become like the radium a benefit for humanity.”