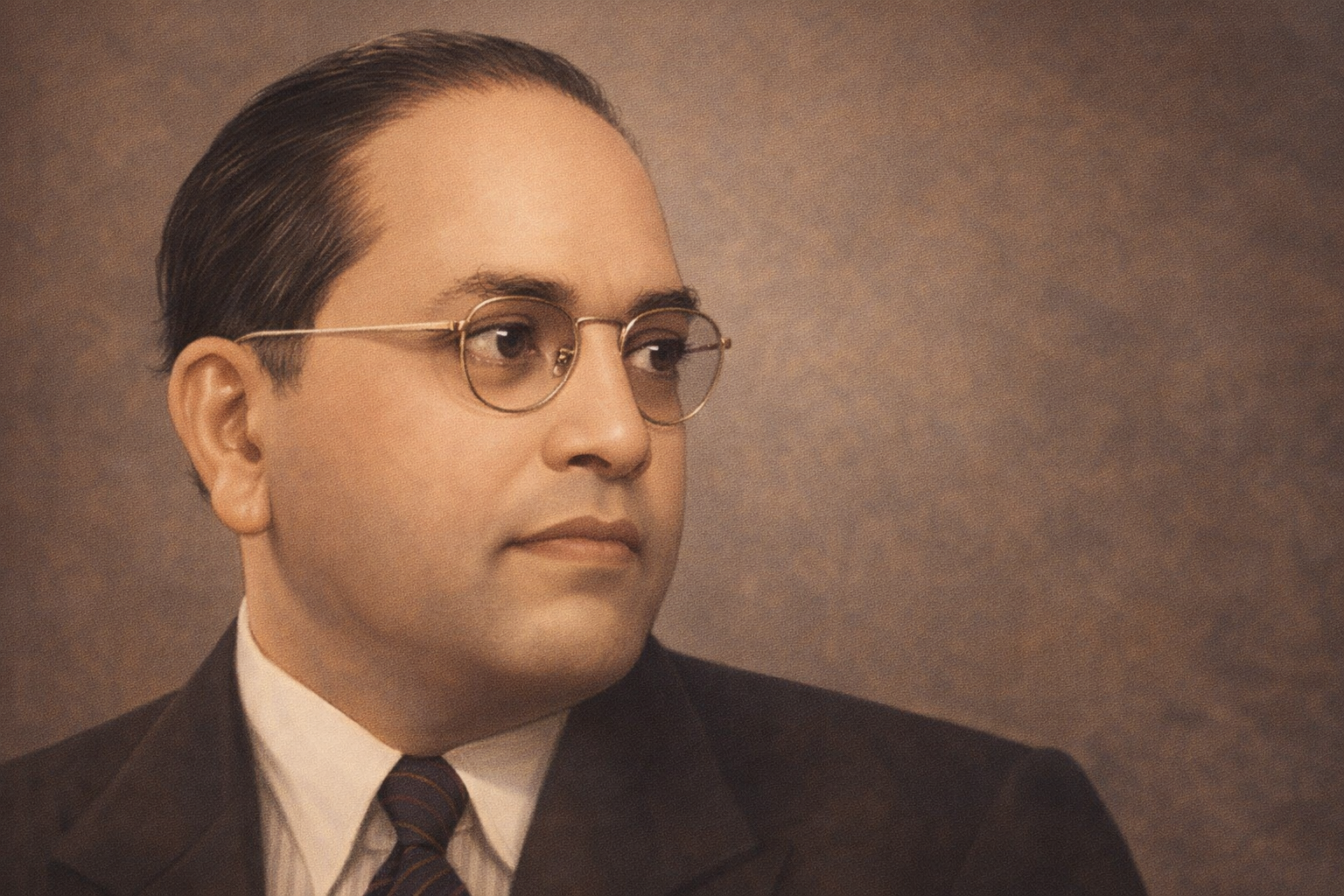

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, popularly known as Babasaheb Ambedkar, was born on April 14, 1891, Mhow (now in Madhya Pradesh) into a Dalit (formerly “untouchable”) family.

He faced severe discrimination and social exclusion from an early age due to the rigid caste system in India. Born into the Mahar caste — in the rigid social order — his earliest memories were marked by exclusion, humiliation, and the heavy chains of caste oppression.

Yet within that boy burned a defiance: that dignity was not a gift from society, but a right to be seized. Despite the hardships, Ambedkar showed exceptional academic brilliance.

Early Life and Education

His father, an army officer, emphasized the importance of education, which deeply influenced young Bhimrao. Denied basic respect in childhood, Ambedkar turned to books as his fortress. Education became his weapon.

From Elphinstone College in Bombay to Columbia University in New York and the London School of Economics, he pursued knowledge with a rare hunger. Each degree was not just personal triumph but an act of rebellion against the very system that sought to confine him.

“I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress which women have achieved.”

Returning to India, Ambedkar became a fierce advocate for the rights of the oppressed — Dalits, women, and labourers. His voice carried the weight of centuries of injustice, and his pen crafted arguments sharper than any sword.

He challenged both British colonial rule and the deep-rooted inequities of Hindu society, believing that true freedom demanded social equality as much as political independence.

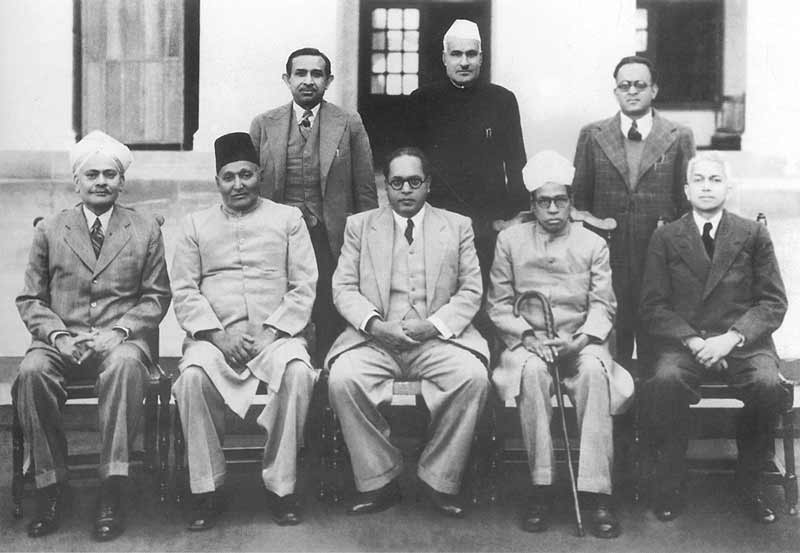

Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution

In 1947, as Independent India sought its foundations, Ambedkar was chosen to chair the Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution.

The result was not just a legal document, but a moral covenant — enshrining liberty, equality, and fraternity as the cornerstones of the Republic.

He embedded safeguards for fundamental rights, protections for the marginalised, and a vision of India that could rise above the old divisions.

“We must stand on our own feet and fight as best as we can for our rights.”

When the British proposed separate electorates for Dalits, Mahatma Gandhi went on a hunger strike in protest. This led to the Poona Pact between Gandhi and Ambedkar. Though Ambedkar was deeply disappointed with the compromise, he agreed for the greater good, securing reserved seats in legislatures instead.

After India’s independence in 1947, Dr. Ambedkar was appointed as the Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution. He played a pivotal role in shaping the Indian Constitution. His vision ensured that India became a sovereign, secular, and democratic republic.

Conversion to Buddhism

In 1956, Ambedkar converted to Buddhism along with over 500,000 followers, seeking liberation from caste oppression. He believed Buddhism represented equality, compassion, and rationalism.

On 6 December 1956, Ambedkar passed away, leaving behind not merely a legacy, but a movement. Statues, books, and countless hearts keep his name alive, but his true monument is the idea he fought for — an India where no human is born lesser than another.

“Life should be great rather than long.”

Legacy

B. R. Ambedkar’s journey — from the margins of society to the heart of its Constitution — is the story of how knowledge can shatter chains, and courage can rewrite destiny.

Ambedkar founded the Independent Labour Party (1936) and later the Scheduled Castes Federation (1942). He also served as India’s first Law Minister in the Cabinet of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

His birthday, April 14, is celebrated as Ambedkar Jayanti, a public holiday and a symbol of equality and empowerment.

In his autobiographical note ‘Waiting for a Visa’, he recalled how he was not allowed to drink water from the common water tap at his school, writing, “no peon, no water”.

Waiting for a Visa

“While in the school I knew that children of the touchable classes, when they felt thirsty, could go out to the water tap, open it and quench their thirst. All that was necessary was the permission of the teacher. But my position was separate. I could not touch the tap and unless it was opened for it by a touchable person, it was not possible for me to quench my thirst. In my case the permission of the teacher was not enough. The presence of the school peon was necessary, for, he was the only person whom the class teacher could use for such a purpose. If the peon was not available I had to go without water. The situation can be summed up in the statement—no peon, no water.

At home I knew that the work of washing clothes was done by my sisters. Not that there were no washermen in Satara. Not that we could not afford to pay the washermen. Washing was done by my sisters because we were untouchables and no washerman would wash the clothes of an untouchable. The work of cutting the hair or shaving the boys including my self was done by our elder sister who had become quite an expert barber by practising the art on us, not that there were no barbers in Satara, not that we could not afford to pay the barber. The work of shaving and hair cutting was done by my sister because we were untouchables and no barber would consent to shave an untouchable.” —Waiting for a Visa

“An ideal society should be mobile, should be full of channels for conveying a change taking place in one part to other parts. In an ideal society there should be many interests consciously communicated and shared. There should be varied and free points of contact with other modes of association. In other words there should be social endosmosis. This is fraternity, which is only another name for democracy. Democracy is not merely a form of Government. It is primarily a mode of associated living, of conjoint communicated experience. It is essentially an attitude of respect and reverence towards fellowmen.” – Dr. B. R. Ambedkar in Annihilation of Caste.