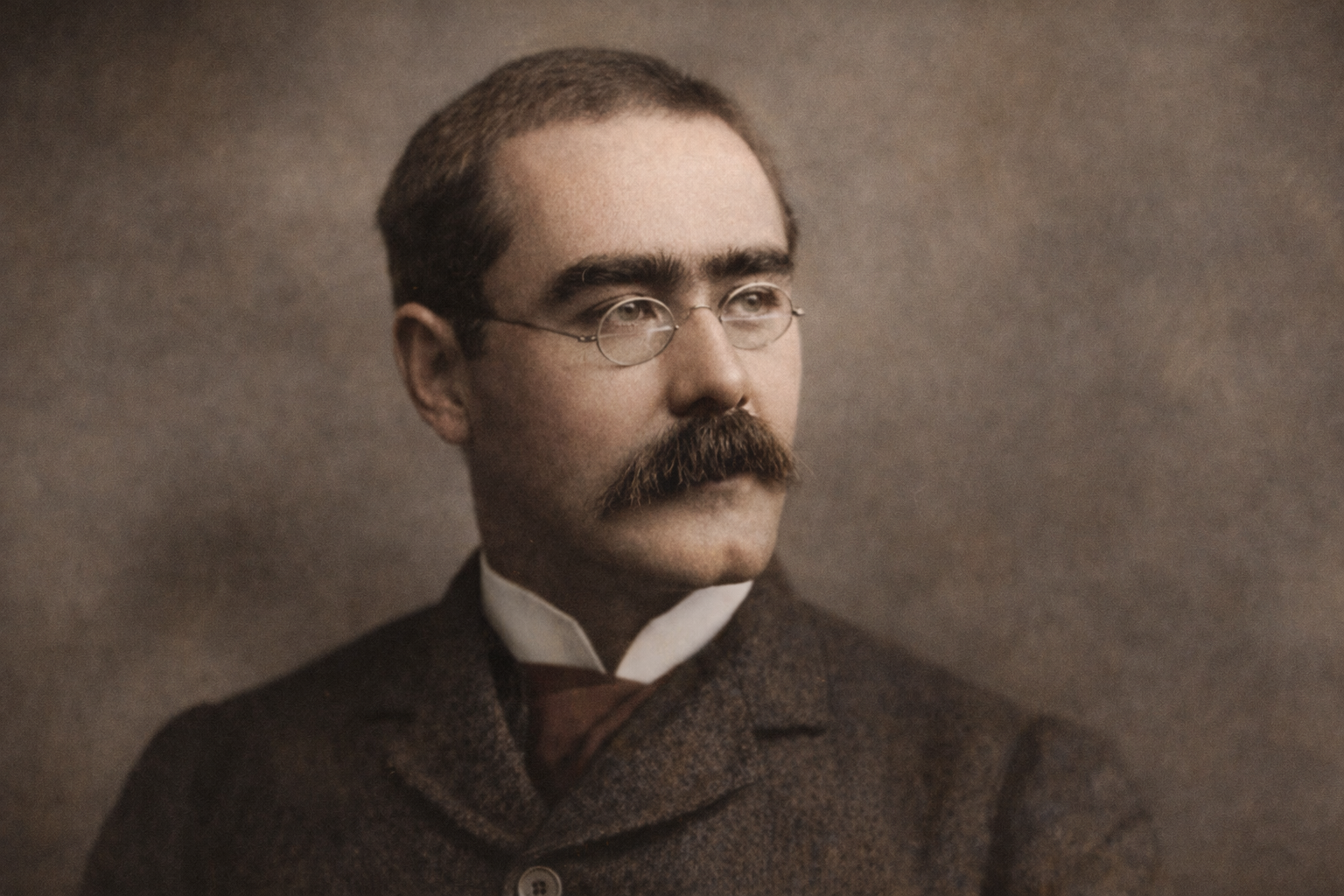

Born on 30 December 1865 in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, Joseph Rudyard Kipling came into the world under the bright glare of the Indian sun, a place that would forever color his imagination.

His father, John Lockwood Kipling, was an artist and museum curator, and his mother, Alice Kipling, a woman of spirited intellect.

In those early Indian days — the monsoon rains, the chatter of bazaars, the rustle of palm leaves — young Kipling absorbed the colors, smells, and languages of the East.

But at just six years old, his life was uprooted. He and his sister Trix were sent to England for schooling. The house they stayed in at Southsea was no haven — he later called it a time of cruelty and neglect.

Years afterward, he wrote,

“I had never forgotten the lessons of those days — that the world is not entirely made up of love and laughter.”

Those hardships etched a resilience into him that would later echo in the stoic strength of his verse.

Return to India — The Awakening of a Writer

At seventeen, his poor eyesight kept him from a military career. Instead, Kipling returned to India in 1882 to work as a journalist in Lahore for The Civil and Military Gazette. India welcomed him back like a long-lost son.

Every street corner, soldier’s tale, and whispered legend became a note in his growing symphony of words. He wrote furiously, publishing short stories that revealed both his affection for India and his sharp observations of colonial life.

“Words are, of course, the most powerful drug used by mankind,”

he famously said — and in India, he became addicted to their alchemy. By his early twenties, books like Plain Tales from the Hills had established him as a voice of the Empire — vivid, unapologetic, and brimming with life.

The Jungle Roars — The Call of Mowgli

In 1894 came The Jungle Book, stories drawn from the forests of India and the whispering wildness of its animals. Mowgli, Baloo, Bagheera — they were more than characters; they were companions from Kipling’s own boyhood dreams.

Children adored them, but the tales carried deeper truths for adults: the balance of freedom and law, the wildness within civilization. He once reflected,

“For the strength of the Pack is the Wolf, and the strength of the Wolf is the Pack.”

That line, from The Law of the Jungle, became a philosophy in itself — about loyalty, unity, and belonging.

London, Love, and Loss

Kipling moved to London in the late 1880s, becoming a literary sensation. He married Caroline Balestier in 1892, and they settled briefly in Vermont, USA.

It was there he wrote Captains Courageous and began Kim, but life was not without tragedy. His first child, Josephine, died from pneumonia at age six — a wound he carried silently.

When asked about grief, Kipling did not speak directly, but his poem If— (written for his son John) carried the echo of loss.

The Nobel and the Shadow of War

In 1907, Kipling became the first English-language writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Swedish Academy praised him for his

“power of observation, originality of imagination, virility of ideas, and remarkable talent for narration.”

Yet even as honors piled up, personal pain deepened. His beloved son John was killed in World War I, a death that haunted Kipling for the rest of his days. He later wrote:

“If any question why we died / Tell them, because our fathers lied.” — a bitter cry from a man who had once championed patriotic duty.

The Final Chapter

In his later years, Kipling’s works shifted from celebration to reflection, grappling with the costs of empire and the weight of memory.

His health declined, and on 18 January 1936, he passed away at age 70, leaving behind a treasury of poems, tales, and imperial chronicles. He rests in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey, alongside the great voices of English letters.

The Legacy

Kipling’s voice is still debated — a master storyteller entwined with the complex legacy of empire. Yet his words endure because they reach beyond politics into the raw truths of human nature: courage, loss, loyalty, and the pull between freedom and duty.

“We have forty million reasons for failure, but not a single excuse.”

And perhaps that is his most enduring gift — the challenge to live with grit, imagination, and a story worth telling.

While he was celebrated as a literary genius, modern critics have also scrutinized his imperialistic tone and portrayal of colonial subjects.

Nonetheless, Kipling remains one of the most influential writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

His stories continue to inspire adaptations in film and literature, and his poem “If—” is still widely quoted for its stoic wisdom and motivational power.

If

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you;

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too:

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or being hated don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise;

If you can dream—and not make dreams your master;

If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim,

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same:

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken,

And stoop and build ’em up with worn-out tools;

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss:

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch,

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you,

If all men count with you, but none too much:

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!

The Law Of The Jungle

NOW this is the Law of the Jungle—as old and as true as the sky;

And the Wolf that shall keep it may prosper, but the Wolf that shall break it must die.

As the creeper that girdles the tree-trunk the Law runneth forward and back—

For the strength of the Pack is the Wolf, and the strength of the Wolf is the Pack.

Wash daily from nose-tip to tail-tip; drink deeply, but never too deep;

And remember the night is for hunting, and forget not the day is for sleep.

The Jackal may follow the Tiger, but, Cub, when thy whiskers are grown,

Remember the Wolf is a Hunter—go forth and get food of thine own.

Keep peace withe Lords of the Jungle—the Tiger, the Panther, and Bear.

And trouble not Hathi the Silent, and mock not the Boar in his lair.

When Pack meets with Pack in the Jungle, and neither will go from the trail,

Lie down till the leaders have spoken—it may be fair words shall prevail.

When ye fight with a Wolf of the Pack, ye must fight him alone and afar,

Lest others take part in the quarrel, and the Pack be diminished by war.

The Lair of the Wolf is his refuge, and where he has made him his home,

Not even the Head Wolf may enter, not even the Council may come.

The Lair of the Wolf is his refuge, but where he has digged it too plain,

The Council shall send him a message, and so he shall change it again.

If ye kill before midnight, be silent, and wake not the woods with your bay,

Lest ye frighten the deer from the crop, and your brothers go empty away.

Ye may kill for yourselves, and your mates, and your cubs as they need, and ye can;

But kill not for pleasure of killing, and seven times never kill Man!

If ye plunder his Kill from a weaker, devour not all in thy pride;

Pack-Right is the right of the meanest; so leave him the head and the hide.

The Kill of the Pack is the meat of the Pack. Ye must eat where it lies;

And no one may carry away of that meat to his lair, or he dies.

The Kill of the Wolf is the meat of the Wolf. He may do what he will;

But, till he has given permission, the Pack may not eat of that Kill.

Cub-Right is the right of the Yearling. From all of his Pack he may claim

Full-gorge when the killer has eaten; and none may refuse him the same.

Lair-Right is the right of the Mother. From all of her year she may claim

One haunch of each kill for her litter, and none may deny her the same.

Cave-Right is the right of the Father—to hunt by himself for his own:

He is freed of all calls to the Pack; he is judged by the Council alone.

Because of his age and his cunning, because of his gripe and his paw,

In all that the Law leaveth open, the word of your Head Wolf is Law.

Now these are the Laws of the Jungle, and many and mighty are they;

But the head and the hoof of the Law and the haunch and the hump is—Obey!